With his unmistakable booming voice and vast red beard, James Robertson Justice was one of the pillars of the British cinema in the Fifties and Sixties.

With his unmistakable booming voice and vast red beard, James Robertson Justice was one of the pillars of the British cinema in the Fifties and Sixties.

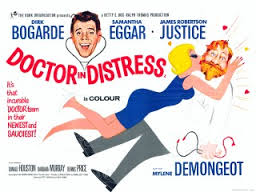

The star of seven Doctor In The House comedies – as surgeon Sir Lancelot Spratt – as well as playing Lord Scrumptious in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, this 6ft 2in, 19-stone actor was larger than life in every sense.

However a new biography reveals, he was also a deeply contradictory and troubled man – a selfish fantasist, an unrepentant socialist who nevertheless drove a Rolls-Royce and was a friend of the Royal Family, a man with a great appetite for food and drink and yet a man who let his mother die from malnutrition, and a relentless womaniser.

For example, Justice always said that he was born underneath a whisky distillery on the Isle of Skye in Scotland – when he was actually born in Lee, South London, and was brought up in Bromley, Kent.

Indeed, he wasn’t even christened James Robertson Justice – only adding the middle name in his late 30s in order to sustain the myth of his being Scottish.

He also liked to boast that he had a science degree from London University and a doctorate in philosophy-from Bonn University, in Germany, when, in fact, he had neither.

Despite such relentless fabrications, however, there was enough in his life to fill several biographies.

Repeatedly during his 30-year career, which included 87 films, this ebullient ginger-haired actor invented endless stories about every part of his life, loving to create mysteries, which his friends claimed was an attempt to conceal the insecurities that lay behind his bluff, rumbustious exterior.

He worked for a time as a reporter for the Reuters news agency, was a teacher in Canada, played professional ice-hockey, drove racing cars, was a member of the German police force when the Nazis came to power, and was a founder member of the late Sir Peter Scott’s Wildfowl Trust – achievements all made before becoming an actor.

A new biography reveals that Justice was a deeply contradictory and troubled man and a selfish fantasist

As his friend, the Duke of Edinburgh, says of him: “James was a large man with a personality to match. He lived every bit of his life to the full and richly deserves the title “eccentric”.”

The two men first met in the Forties and shared a love of hunting with falcons in Scotland – a passion that Justice later helped to pass on to Prince Charles.

So let us try, 33 years after his death at the age of 68 in 1975, to unravel the truth about this contradictory man.

One thing is clear above all others about the blustering, often rude, Justice – he never cared to be thought of as a film star.

“I am not a star!” he would insist, often at the top of his voice. “I am in this profession to make money.”

As Richard Gordon, author of Doctor In The House, puts it: “He preferred to think of himself as a straightforward Scotsman who wore kilts, fished the lochs, flew falcons and knew those people over at Balmoral. Every performance was himself.”

To understand the real James Robertson Justice, we need to return to his South London birthplace in June 1907, where he was the only child of a geologist who, ironically, despised everything about the Scots, even though he’d been born in Aberdeen.

His father, also called James, saw little of his son, as he was travelling the world.

By the time he returned to England in 1922, young James was already a boarder at Marlborough school in Wiltshire.

Not that Justice ever talked about his childhood. As his biographer, James Hogg, puts it: “Perhaps the absence of his father for long periods was too deep a wound to revisit.”

But this was not the only part of his life that he liked to draw a veil over.

After Marlborough, Justice studied science at University College, London, but left after a year in mysterious circumstances and became a geology student at Bonn, where he acquired an appetite for languages, but left equally suddenly to return to England in the summer of 1927.

Still only 21, it wasn’t long before he secured a job at Reuters news agency in London, where another reporter was the young Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond.

His friend, the Duke of Edinburgh, said that Justice was ‘a large man with a personality to match’ and ‘lived every bit of his life to the full’

But Justice was useless at the job. One colleague called him “quite unsuitable” – not least for his habit of turning up for a night shift in dressing gown and pyjamas.

After a matter of months, he then set off for Canada, where he sold insurance, taught English at a boys’ school, became a lumberjack and mined for gold.

Feeling homesick, Justice worked his passage back to England by washing dishes on a Dutch freighter – or so he later maintained – and by 1931 he was playing for the London Lions ice-hockey team – another career that lasted barely a year.

Undeterred, he tried his hand at motor racing, entering a race at Brooklands in Surrey.

But, characteristically, he disappeared again – to become a policeman for the League of Nations in the Saar area of Germany.

Mystery surrounds this brief period in his life. One suggestion was that he was forced to leave after firing into a hostile crowd and killing someone with the ricochet.

Then there was his subsequent war service with the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, which also came to an abrupt halt for no clear reason in 1943, although there were rumours of a knee injury from a German shell.

We next discover Justice, having married, living part of the year in Wigtown, Scotland, shooting geese and driving a Rolls-Royce.

It was at about this time that his acting career began and all the unanswered questions about his early life were quietly swept into the background.

Typically, Justice took up acting by accident after a visit to the Players’ Club in London on one of his regular visits south.

The Players’ regularly restaged Victorian music hall nights under the chairmanship of the late Leonard Sachs, who was later to reprise the role on BBC television’s The Good Old Days.

Justice managed to stand in for Sachs on one occasion, and on the strength of that performance was recommended for a part in a film, For Those In Peril, in the summer of 1944.

He was 37, and, within four years, Justice was playing a leading role – that of the headmaster in the film Vice Versa, written and directed by the then 26-year-old Peter Ustinov, who cast him partly because he’d been “a collaborator of my father’s at Reuters”.

After that, Justice was given a contract by the Rank Organisation. By then, he’d added Robertson to his name.

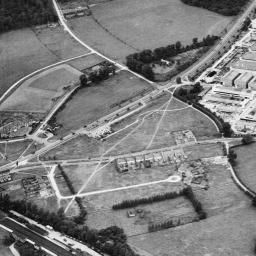

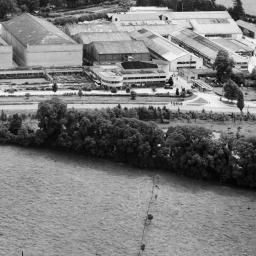

Ken Annakin recalled working with James Robertson Justice during the making of ‘The Story of Robin Hood’ . Justice he said could, with careful direction always be relied upon to ‘add verisimilitude’ (as he used to say) to any larger than life character. For three weeks he and Richard Todd rehearsed the famous quarter-staff fight scene on a wooden bridge built over the studio tank at Denham Studios. They rehearsed with Rupert Evans the most expert sword master and ‘period’ fight arranger in England at the time.

After a lot of lively exchanges of blows, Richard Todd was knocked into the water as scripted and Justice jumped in after him. Without a break they continued to parry and thrust, as choreographed, until Richard trod on a nail which penetrated his thin deer skin boot.

“Shit!” he yelled, and losing his balance, swiped James a mighty blow across the head.

Justice cried out “Foul, not fair!” and disappeared under the water only to reappear, spluttering “varlet!” still in character. “Have you no respect for the pate of a philosopher! If you’ve damaged the old brain box, Edinburgh University is going to lose its most distinguished Rector!”

It was true, Justice had just received a phone call in his dressing room, offering him the honour-something unheard of in the acting profession.

Shortly afterwards, he was introduced to Prince Philip.

The two men became members of the infamous Thursday Club which met for lunch in Soho in the late Forties.

Other members included David Niven and Peter Ustinov.

But it was through the club that Justice met one of the first of his many female conquests, even though his wife (former nurse Dilys Hayden, whom he’d married in Chelsea in 1941), had given birth to their son, James.

He would take great delight in parading around his young mistress’s flat wearing only a sporran while playing the bagpipes.

Justice took up acting by accident after a visit to the Players’ Club in London on one of his regular visits south

His success as Dr Maclaren in the 1949 Ealing Comedy Whisky Galore, cemented his reputation and enabled him to buy a mill house in Hampshire.

But, sadly, it was to become the scene of tragedy just a few months later, when his four-year- old son was drowned there.

His wife blamed him for not fencing off the stream that ran beside the house, but, typically, Justice would only tell his friends: “I don’t talk about it.”

By now, his career was taking off and the role of the demanding surgeon Sir Lancelot Spratt in Doctor In The House turned him into an international star.

The film sold 17 million tickets in Britain in 1954, making it the most popular film of the year.

It also helped to spawn the Carry On series, which was launched four years later.

Justice’s fee allowed him to buy a bungalow in the village of Spinningdale in Scotland, which was to be his home for the next two decades – and where he indulged his passion for collecting hawks, moths and orchids.

However the actor’s selfish streak remained. After his father’s death in 1953, Justice’s mother, Edith, had gone to live in Hampshire, but her only son was conspicuous by his absence.

Indeed, despite his own vast intake of food and fine wine, she was to die of malnutrition just a few years later – a “very sad and undeserved end”, in the words of one local who knew her well.

Justice relished his reputation for eccentricity, taking pleasure in waking guests at his Scottish home by playing Mozart’s horn concertos on a length of garden hose which he kept especially for the purpose.

His appetite for young women hadn’t dimmed either, and, in the mid-Fifties, he pursued the painter Molly Parkin, then a young art teacher but later to become one of the most renowned fashion journalists of the Sixties.

He was almost 50, and still, legally, a married man.

Justice wanted to marry Parkin and have children – in particular, another son – but she refused, and the relationship withered.

Accepting the inevitable, he and his wife officially separated in 1958.

Justice continued to have a procession of affairs with his leading ladies – including one with the married actress Irina von Meyendorff, who’d appeared opposite him in The Ambassadress.

By 1967, the couple were living together, and the following year, during his eventual divorce from the long-suffering Dilys, she was cited in court papers.

But Justice refused to marry her, even though he called her his “great love”.

Not long after completing Chitty Chitty Bang Bang in 1968, however, Justice suffered a severe stroke, and the following year, his career was over.

As his new biographer puts it: “The boisterous, larger-than-life figure of just a few years before was gone, he was a shadow of his former self.”

He was to suffer a further series of strokes, which served only to make him even angrier. Frustrated at his incapacity, he would take his anger out on Irina.

Yet, ironically, it was his former wife who brought his final humiliation – suing him for his failure to pay the £50-a-week maintenance he’d promised. She forced him into bankruptcy and into selling his beloved home in Scotland.

Now destitute, it was his friend, Toby Bromley, heir to the Russell & Bromley shoe fortune, who saved him – offering Justice a cottage on his Hampshire estate, where the two men went on to make two wildlife documentaries about their love of falcons and trout fishing.

But by then, according to fellow actor Leslie Phillips, “his mind had very little control over his body” and Justice was suffering “bouts of depression and loneliness”. This once irrepressible figure was reduced to sitting immobile in his chair, furious at his inability to make an impact on life.

Then, in a final twist to the drama of his life, on June 29, 1975, and knowing that he was dying, James Robertson Justice married Prussian-born Irina who had suffered his selfishness for so many years. Just three days later, Justice, a crippled, penniless ghost of his former self who was nevertheless remembered by so many with such pleasure, was dead.

It was a miserable end.

This film from 1957 was on the Sky Film Channel yesterday February 15th 2014, and I watched some of it and was impressed by the colour and the scale of the production but straight away I noticed the supporting actors – Robert Beatty, Wilfred Hyde White, George Coulouris and Peter Arne – Yolande Donlan and Betta St John – all British actors although Yolande was from the US but had settled here and so I think had Betta St John who had married an English actor. On checking I see that the film was made on location in Africa with the studio work done at Elstree in England. There was a lot of studio work and a lot of it is on large sets of ‘outdoor’ jungle locations – which I have to say were very impressive.

This film from 1957 was on the Sky Film Channel yesterday February 15th 2014, and I watched some of it and was impressed by the colour and the scale of the production but straight away I noticed the supporting actors – Robert Beatty, Wilfred Hyde White, George Coulouris and Peter Arne – Yolande Donlan and Betta St John – all British actors although Yolande was from the US but had settled here and so I think had Betta St John who had married an English actor. On checking I see that the film was made on location in Africa with the studio work done at Elstree in England. There was a lot of studio work and a lot of it is on large sets of ‘outdoor’ jungle locations – which I have to say were very impressive.