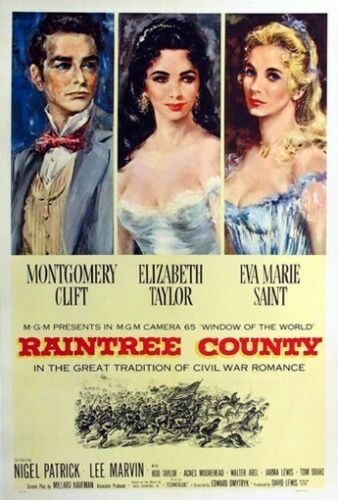

Raintree County (1957)

In 1949, upon the release of The Heiress, Paramount Pictures demanded that Montgomery Clift do his share to promote the film. Stars were expected to do so, even those as difficult as Monty. It was through these promotional machinations that the actor found himself with a date for the premiere of the film. Though he would always call her Bessie May, the girl the studio had paired with Clift was none other than grown-up child actress Elizabeth Taylor.

This “date” was a multi-purpose arrangement. Elizabeth Taylor was looking to be seen as an adult after having established herself as a starlet during her girlhood. Her pairing with Hollywood’s hottest new property made her look more womanly to moviegoers. Also, since A Place in the Sun was already in development, Paramount was prepping the audiences to see this romantic couple illuminate the screen. The two rising stars were chaperoned by Clift’s acting coach, Mira Rostova, and they hit it off right away.

Supposedly, Monty was instantly charmed when, before the premiere, Liz insisted they stopped at a burger joint to fill themselves with a bit of tasty greasy food in preparation for the red-carpet spectacle. Still, what blossomed out of that evening wasn’t a romance, but a lifelong friendship. He stuck with her through thick and thin, through endless scandals, and five failed marriages. As for Taylor, she saved his life.

After From Here to Eternity, Montgomery Clift dropped out of Hollywood for a couple of years. He had started drinking and taking pills at the end of the previous decade and, by the mid-50s, he was an addict with a reputation to match. Along with his pickiness, this made him victim to the dangers of career stagnation as well as increasing debts. Knowing all that, Liz Taylor is said to have convinced MGM to sign Monty to a three-picture deal.

The first of those projects would be Raintree County.

The picture, which was the latest attempt at making “the next Gone with the Wind“, had a famously large budget. MGM splurged on the Civil War melodrama, making it the most expensive film ever shot exclusively on American soil up to that point in history. Production started according to plan in the first half of 1956 and, by early May, the interior scenes had been filmed in Hollywood. Afterward, the production was scheduled to go to Kentucky where exterior shoots would take place.

They were meant to fly on a Sunday to Kentucky. On Saturday, May 6th, 1956, Liz Taylor threw a grand dinner party. She had to cajole Monty into coming as he was reluctant. So vehement was he that he wanted to stay home that Monty had dismissed his chauffeur. As a consequence, when his friend succeeded in convincing him, Monty had to drive himself to Liz’s mansion. By all accounts, he only drank a glass and left early, sober, and tired.

What happened next is the stuff of nightmarish Hollywood legend.

Kevin McCarthy, Monty’s dear friend who had been driving ahead of him was the one to sound the alarm. He returned to Taylor’s mansion crying about a car accident. Clift had driven off the road and into a telephone pole, smashing his car and himself in the process. Remembering that tragic evening, McCarthy would be quoted as saying “his face was torn away—a bloody pulp. I thought he was dead.”

The men tried to prevent Liz from seeing Monty mauled, a mask of torn flesh and broken bone where the visage of Hollywood’s most handsome star used to be. Nobody could stop her, though. Cradling her bloodied friend, Liz reached down into his throat and pulled out Monty’s front teeth that had been knocked off by the crash and were choking him. He would have died if it weren’t for Liz, who also made sure no photographs were taken of his wrecked state.

Every bone in the actor’s face was mangled, his nose broken and his jaw torn to pieces. While he recuperated, production on Raintree County was shut down temporarily. One might wonder why MGM didn’t just recast the role. For starters, the film was already a huge expense and most of the actors agreed to have their pay cut to allow for the needed delays in shooting. Also, Taylor would have walked off the project if MGM dared to replace Monty, ruining any hope at recouping their investment.

And so it was that Montgomery Clift returned to Raintree County after laborious reconstructive surgery and physical therapy. Director Edward Dmytryk tried his best to hide the sorry state of his leading man, shooting him predominantly in profile and using shadows to mask the truth. Nonetheless, Clift’s face changes noticeably from scene to scene, sometimes varying wildly in a short time.

His lip was freshly sewn up, his jaw still wired together, so brittle that it made alarming sounds when he tried to move it too much. He couldn’t eat either and was in constant pain, suffering from insomnia and recurring nightmares which plunged him in a state of perpetual exhaustion. Furthermore, a nerve on the left side of his face had been severed, partially paralyzing his muscles. It’s not that he looks ugly, just that he looks off and inconsistent throughout. How can we expect someone to give a good performance under those circumstances?

The drinking didn’t help matters either. Clift was so often intoxicated that the cast and crew developed a code to signal each other about his current state – Georgia meant he was bad, Florida was worse, Zanzibar was catastrophic. By all accounts, the second half of the shooting of Raintree County was a nightmare for everyone involved and, at the end of it, Clift described the movie as a bloated mess. He wasn’t wrong.

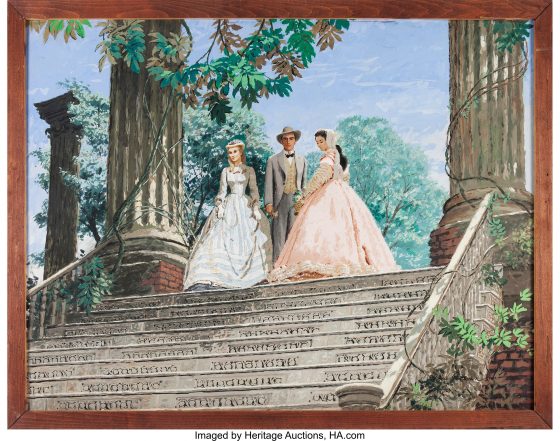

Aside from the horror story happening behind the scenes, Raintree County is a hapless epic whose sense of desperate prestige is too grand and obnoxious to bear. It’s a self-conscious movie, so preoccupied with being perceived as good that it forgets to be so. Even its glamour is over-calculated, with Walter Plunkett’s monstrosities of wide crinolines and corseted waists parading through the screen with evident opulence but little storytelling purpose.

The narrative, adapted from a novel by Ross Lockridge Jr, attempts to portray America’s Civil War schism. It centers on Clift’s John Shawnessy, a studious Yankee who happens to fall in love with a vivacious Southern Belle, Taylor’s Susanna Drake. He marries her, turning his back on fellow abolitionist Nell Gaither with which he had a kindling attraction, and finds himself embroiled in his wife’s spiral of self-hatred, racism, hidden secrets, and barely contained psychosis.

As the war roars and Susanna’s mental health goes down the drain, John becomes a soldier, another military man in Clift’s filmography. He sees horrors and, once the conflict is over, returns to his studious ways, becoming a teacher whose company incentives to follow a career in politics.

Pedagogue, warrior and leader, devoted husband, and tragic lover, John is actually a complicated character whose torments are plenty and whose interiority is a fascinating conundrum. You wouldn’t necessarily know that by suffering through the picture’s torturous three hours. Clift sleepwalks his way through the picture and only some pre-accident scenes ring with vitality. Among them is a lively ball and the first taste of alcohol where a nervous energy coalesces into comedic verve cutting a temporary hole in the funereal seriousness of Raintree County. There is also some electric charge in most of his scenes with Taylor, even when the turgid drama is otherwise as lifeless as a taxidermized critter.

What we know of the stars helps the movie achieve its slivers of watchability. John and Susanna hardly seem to make sense as a couple and we often wonder why he stays with her apart from the chains of the social norm. His devotion, as defined by the script, runs deep but that rarely registers in the performances, only through the metatextual reading and chemistry that the movie stars bring to the project.

Raintree County is the nadir of Montgomery Clift’s career as a movie actor, but there’s still some faint value to be found within its depths of mediocrity. As the actor himself had predicted, it was a success among audiences, though its high cost meant that MGM still reported a loss. Many were sure to have played a macabre game of ‘spot the difference,’ gazing in terrified awe at the new face of Montgomery Clift.

One should acknowledge that Clift already looked and acted differently from what people expected in the pre-accident scenes. In the years since From Here to Eternity, Clift’s drinking had spiraled out of control. Christopher Isherwood wrote that, by 1955, the actor was “drinking himself out a career”. It had been four years since audiences had seen him and Clift looked like he had aged over a decade, and the intense energy he once brought to the screen was gone, even if only temporarily.

Montgomery Clift was never the same after the accident, but he and Liz Taylor remained loyal, devoted friends. Their third and last movie together is still up ahead but, even beyond ‘Suddenly Last Summer’ – they were a constant in each other’s lives. Unlike Monty’s career, that friendship was a straight continuous line that only ended in death. Professionally, however, the legacy of the actor is broken into two violently divided halves.

Raintree County marks the beginning of the second era of Montgomery Clift as a film star. It’s the beginning of the end.

Much of the above – not all – is taken from another Blog

Place your comment