What an influential man he was in the British Film Industry in fact no other person is associated more with the era of British Film making just before and after the War than he was. He was the Head of Ealing Studios and later took charge of MGM British Productions – a most prestigious job. He had seen success and disappointment over his period at the heart of British Films.

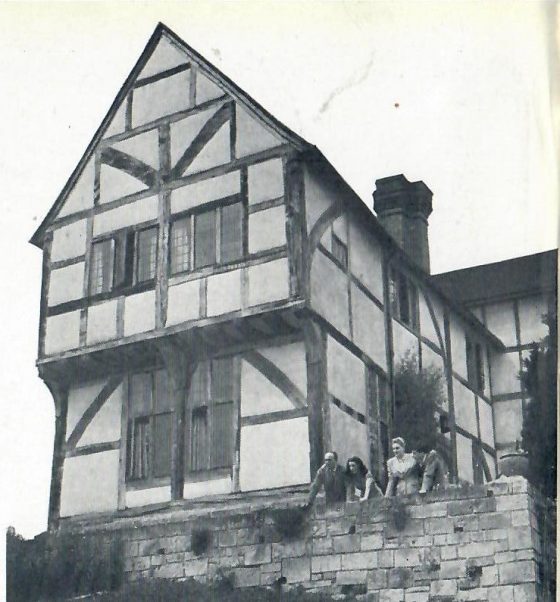

Michael Balcon at Home Her bought this Farm in Sussex on the Kent border in 1946 at Upper Parrock. He spends the week in a suite high up in a London Hotel and returns to his home at the weekend.

Here he is with his son, Jonathan

Michael Balcon and family enjoying the view on a Summer evening

Michael Balcon with his Daughter Jill Balcon – with whom he later had a poor relationship because of the man she decided to marry.

Mrs Balcon at Home – formerly Aileen Leatherman – who comes from a well-known Johannesburg family. She was awarded and MBE for her work in the Red Cross during the War – not long ended when this picture was taken

Michael Balcon at Home with his family

Sunday afternoon relaxing ABOVE

ABOVE – Aileen is in charge of all farming matters

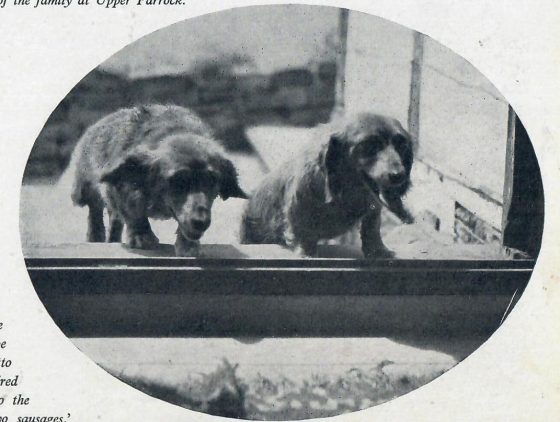

ABOVE – Otto and Gretel long haired dachshunds known in the household as ‘the two sausages’

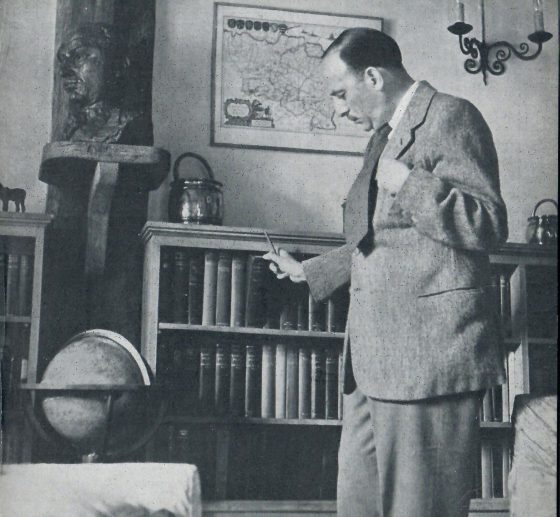

Michael Balcon at Home in his library

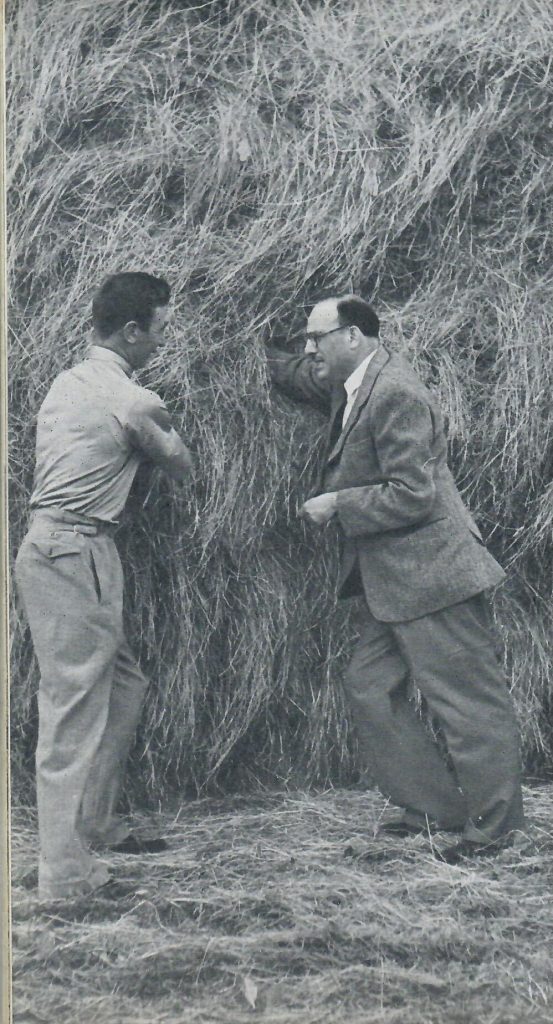

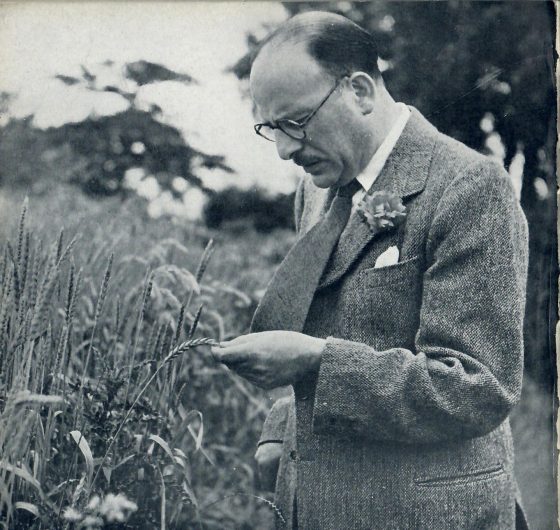

Michael Balcon seeking advice of farming matters

Michael Balcon ABOVE – He says that he is posing trying to look intelligent about the corn, but as he admits all he knows about this field is that it was badly damaged in the 1946 harvest

Michael Balcon loved his home here and he died here in 1977, his 15th-century house set on a Sussex hilltop near the Kent border. He and his wife had lived there since the Second World War. He was cremated and his ashes buried there

BELOW – A Much Later interview with his Daughter Jill Balcon

When she wed the future poet laureate C Day-Lewis her parents disowned her, wary of his reputation as a womaniser. The actress has rarely talked about her marriage, but as a new biography of her husband is published, she tells of their love, their children Daniel and Tamasin, and the hurt she still suffers

Jill Balcon, clear-sighted and with an actor’s eye for the telling detail, is a thrilling repository of stories about a world that now only exists among the pages of biographies. To her, WH Auden is better known as Wystan, Vaughan Williams as Ralph.

Jill Balcon rarley talked about her past for a long time. The last biography of her husband, poet laureate C Day-Lewis, appeared in 1980, eight years after his death from cancer at the age of 68. It was written by his son, Sean (by Day-Lewis’s first wife, Mary), and it caused his widow great pain (mistresses were alluded to and the poetry all but ignored). She vowed, thereafter, to keep her silence, though she and Cecil, somewhat to her discomfort, would occasionally appear in biographies of other people, those of Cecil’s lovers, mostly.

Now, though, she has helped another biographer, Peter Stanford, to write her husband’s life. ‘I’m very two-faced,’ she says, with a short laugh. ‘I love reading biographies.’ And what does she make of this one? It is good, meticulous and pays proper attention to the poems, which she longs for people to rediscover (difficult to believe now how admired Day-Lewis once was; in 2007, he is ignored, not even honoured in Poet’s Corner).

She fears it will again be his private life that is most picked over and she is right. Serialised in another Sunday newspaper, the headline is a gruesome: ‘The Laureate of Lust’. Oh, well. I suppose we still expect only two things of our poets: that they be poor, and that they have complicated sex lives.

In any case, these things are relative. Day-Lewis’s private life was difficult but only by the standards of the day; he would barely make the cover of Heat now. Stanford suggests that Day-Lewis had two illegitimate sons in addition to the four children he had in marriage (two sons by Mary, the daughter of his old school-teacher, whom he married in 1928, and then, by Jill, Tamasin, the famous food writer, and Daniel, the even more famous actor), but they were

Stanford also details the poet’s already well-known relationship with novelist Rosamond Lehman, with whom Day-Lewis set up home in London while still married to Mary. After marriage to Balcon in 1951, there were more infidelities of the heart – we’ll come back to the most serious of these – but some may have been unconsummated (he was close to the young AS Byatt, but Stanford doubts that they slept together).

It is not, with Day-Lewis, a numbers game: it was his timing that was scandalous. Liaisons would happen when his children were small, their mothers tired and distracted. Or, paralysed by indecision – Lehman called it his ‘aspen hesitation’ – he would try desperately to keep two women content and end up hurting both of them horribly.

Jill Balcon met Cecil Day-Lewis in 1948, in a studio for the BBC’s Time for Verse. She had recently made her screen debut as Madeline Bray in an adaptation of Nicholas Nickleby. She thought Day-Lewis had not noticed her – he was, after all, 21 years her senior – but he had. How could he not? The only daughter of Michael Balcon, head of Ealing Studios, Balcon was magnificent. ‘She looked like the sort of woman you only see on a Greek vase,’ says her friend Natasha Spender.

Later that year, after only a handful of meetings, they fell in love and Day-Lewis left both his wife of 21 years, Mary, and his lover of nine, Rosamond Lehman (the latter was furious – her sense of betrayal at what she regarded as an ‘infatuation’ was so deep it drove her half mad; she never really recovered). It was not the easiest start to a relationship: financially, Cecil was hard-pressed – he still had his children to keep – and Lehman was vilifying him to anyone who would listen. Plus, there was a divorce to be organised, a sordid business in those days. Then there was Jill’s father, who was implacably opposed to the relationship.

‘We started living together,’ says Balcon. ‘For a long time, we thought we’d never be able to marry. My father, who saw everything in black and white, was tremendously hostile. “There’s no reason why he’ll ever get a divorce,” he said. “What will she [Mary] gain?” Cecil was an older man, he was poor, and the idea that I should be working! My father thought Cecil was degrading me. The people who worked for him at Ealing, their private lives were in turmoil. But when it came to the hearth: the Jewish patriarch, the elder daughter who was rebellious … the fact that for one night I appeared on the front of the Evening Standard as co-respondent in a divorce was so shocking for him. He wanted some rich industrialist [for me], something I would have hated. He wanted to direct my life. When the war started, I was called up. He couldn’t control that. I’ve often thought that no matter how ghastly it [the Blitz] was – some things we went through were very frightening – at least it enabled me to get away.’

When she and Cecil were married, her father attended neither the wedding, nor the reception upstairs at the Ivy. ‘I still mind about that,’ she says, softly. ‘He was a powerful man. My mother met me in secret. We used to sit in her car in Hyde Park.’

Things went from bad to worse. After Tamasin was born, neither of Jill’s parents came near her: ‘No flowers, no message, no mother at the hospital.’ Her father took it as a deliberate slight that, when Day-Lewis placed a birth announcement in the Times, he did not put the words ‘nee Balcon’ after Jill’s name. Years later, they did not even come to Cecil’s funeral.

Still, she does not regret any of it. How could she? ‘Cecil was dazzling. Absolutely mesmeric. He had colossal magnetism. He was beautiful to look at and tremendously funny. So I was prepared to go through any kind of hell. I’ve got his letters and I discovered after he died that he’d kept mine. I don’t know if I have the courage to burn them; I think I’ll ask my son to do it.’

She spent the early days of their relationship feeling an odd combination of incredulity and anxiety. She had married her ‘hero’, a man she’d admired since 1937 when Day-Lewis judged the verse-speaking competition at her school, Roedean, but she was troubled by the circumstances of their meeting – Day-Lewis was emotionally exhausted by the years of shuttling between placid Mary and clingy Rosamond – and worried about money. ‘In those days, alimony was a third of your income.’ In August 1951, invited to join Stephen and Natasha Spender for a holiday on Lake Garda, she and Cecil had to sell two silver coffee pots, a present, in order to pay their fare.

Was she anxious about being a step-mother, too? ‘Of course. But they [Nicholas and Sean] were very nice to me. They couldn’t have been nicer. I think Sean may now feel resentful on behalf of his mother, who was a very good woman, utterly so. But she preferred women, as you probably read; the boys knew it, and Cecil knew it.’

She and Day-Lewis bought a house in Greenwich and tried to get on with life. They shared a love of poetry, their leftist politics (Day-Lewis was an ex-communist) and a sense of humour. But he had his dark side. ‘I’ve lived among writers and poets all my life and nothing is simple. They do tend to be melancholy. He was very often very depressed. Very low and full of guilt. But the thing that was wonderful was when he was composing – then he was happy. To be in another room, to hear him tapping and then for him to say, “This is what I’ve done.” It was so exciting. Like being in the sun. But I was also pitched into a world of older people of whom I was quite nervous.’

Gossip, mostly perpetrated by Lehman, didn’t help. When she was writing Lehman’s biography, Selina Hastings took Balcon to lunch. ‘She told me she thought she was going to be giving lunch to the Witch of Endor. She’d heard all about me from Rosamond.’ Balcon thinks now that perhaps she was naive. ‘Knowing his history [the tangled web with Rosamond], I thought he wouldn’t want to get involved with other people. I like attractive people; not just sexually attractive, but attractive. But if you do, other people are going to find them so, too.’

Balcon did not find out about her husband’s affair with her friend Elizabeth Jane Howard until after it was over, but it hurts her still. In 1954, Chatto & Windus, where Day-Lewis worked part-time as a reader, employed Howard, an actress turned acclaimed novelist, as an assistant. She and Balcon had known each other since their days at the BBC during the war. Howard was famously beautiful and, one night while Balcon was away – she had gone to a party to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Bristol Old Vic – Howard and Day-Lewis went to Dedham Vale on the Essex border to pay homage to John Constable (Day-Lewis recorded this in a poem, ‘Dedham Vale, Easter 1954’). ‘I tried, but I didn’t have the strength to resist him,’ Howard tells Peter Stanford. ‘I would defy any woman to resist him.’

Their affair lasted three months. It was Howard’s guilt that prompted her to finish it, a decision she claims dented her lover’s ego and made him angry and abusive. In her 2002 memoir Slipstream, Howard describes her betrayal of her friend as ‘one of the worst things I ever did’. Tamasin Day-Lewis, her god-daughter, was only a baby at the time. ‘It still haunts me,’ says Balcon, closing her eyes. ‘It comes back and hits me, often at night. I’m so appalled, even all these years on. I think: how could they? I’ve not gone off with my best girlfriend’s men. Ever. When she first told me that it was her who stopped it, that he didn’t want to, well, that was even worse, in a way. I don’t know if it’s the truth because I can’t ask him. It’s terribly painful because we were close friends from being teenagers.’

Balcon looks drained as she tells me this, which makes it even more extraordinary to me that her husband later died in the Hertfordshire house, Lemmons, owned by Howard and her then husband, Kingsley Amis. Balcon took the decision to move the dying Cecil there because it was near Elstree, where she was filming, and because a ground-floor bedroom, complete with nurse, was available (Howard’s mother, Kit, was also ill). But even so …

‘It was a practical arrangement,’ she says. ‘I could be at his bedside in 15 minutes from the studio.’ But why did Howard even dare to suggest it? ‘Part of it was guilt. She saw the state he was in, and … she felt guilt. She must have.’ Yet their friendship continued. They had lunch only last year. ‘Yes. She was Tamasin’s godmother. She had so many lovers, you see. The whole lot. She was so beautiful and charming and gifted and amusing, and he [Cecil] liked people to write good books, which I certainly couldn’t. She told Peter [Stanford] that he’d been in love with her for ages. I find that unbearable because it was not long after we’d struggled to get married.’ She hasn’t read Slipstream and never will.

Balcon was absolutely stricken at Cecil’s death, a widow at just 47. Daniel was still at school, Tamasin was about to take up a place at Cambridge. ‘Our doctor said, “You must never take away hope from a patient”, so he wouldn’t let me discuss what was happening with Cecil. That wouldn’t happen now and it was a terrible burden. I was desperate. I used to take the car down to Deptford Creek and just shriek! I didn’t know what I was going to do for these children. All widows worry about money whether they’re well off or not and I wasn’t. I knew we couldn’t go on living in our lovely house. I mind terribly that he never saw the children growing up. They were at their most tortured and teenage, a terrible time to lose a parent. I don’t think I was at all good with them. I was probably selfish in my own grief.’

What effect did his death have on them? ‘Terrible. Terrible. Terrible. Tamasin’s face got smashed by a train door, Daniel took some migraine tablets that had a very bad effect on him and the school doctor put him in some hospital down in Portsmouth. But these things happen. I feel sorrier for women who’ve been overprotected by their men – you know, who’ve never written a cheque. That’s cruel. I’d written plenty.’

We go into the kitchen for lunch, passing a teenage self-portrait by Daniel – cheekbones like daggers! – and the cartoon Ronald Searle gave her as a wedding present. We eat at a table and chairs that Daniel made for her years ago. Stuck to a counter is a poster for his 1988 film Stars and Bars; by it is a pile of Tamasin’s cookery books. When I tell her that Tamasin’s recipe for lemon risotto is the world’s best, she lights up. But she’s not some sentimental granny.

What I like about Balcon is this: unlike lots of women her age, with aching bones and a too-long widowhood behind them, she has not given up. She’s still present. She’s still interested. We talk – about being single and how vile Couple World can be – and the years between us fall away. And whatever happens to her husband’s poems, however little or much they are read, they are a comfort to her. In this sense, she is luckier than most widows – he’s still around. ‘It sounds awful, but I’m the keeper of the flame. But I grieve when his name isn’t mentioned.’

There are consolations. ‘Daniel [who lives in Ireland with his wife Rebecca Miller, daughter of the playwright, Arthur] was asked to do a village memorial for people who fled the Great Hunger, and chose to read from The Whispering Roots [Cecil’s last collection]. He asked my advice, which normally I wouldn’t presume to give him. So, yes, we are lucky.’ In spite of herself, she smiles.

Michael Balcon at Hom

… [Trackback]

[…] Info on that Topic: filmsofthefifties.com/michael-balcon-and-his-family-at-home/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here on that Topic: filmsofthefifties.com/michael-balcon-and-his-family-at-home/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: filmsofthefifties.com/michael-balcon-and-his-family-at-home/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 62038 more Info on that Topic: filmsofthefifties.com/michael-balcon-and-his-family-at-home/ […]