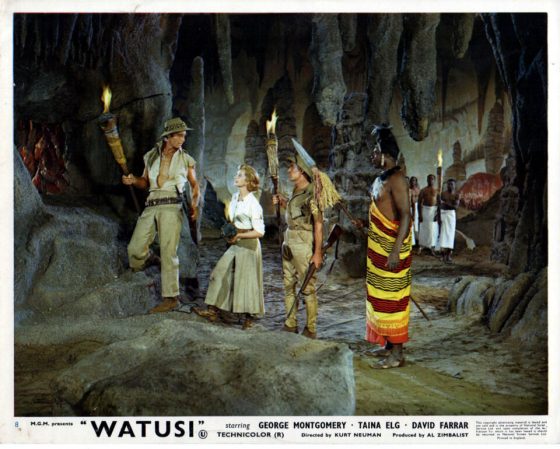

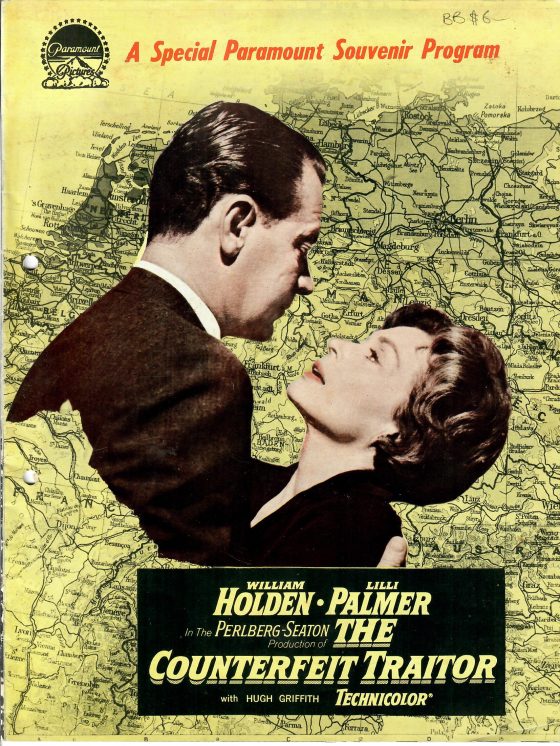

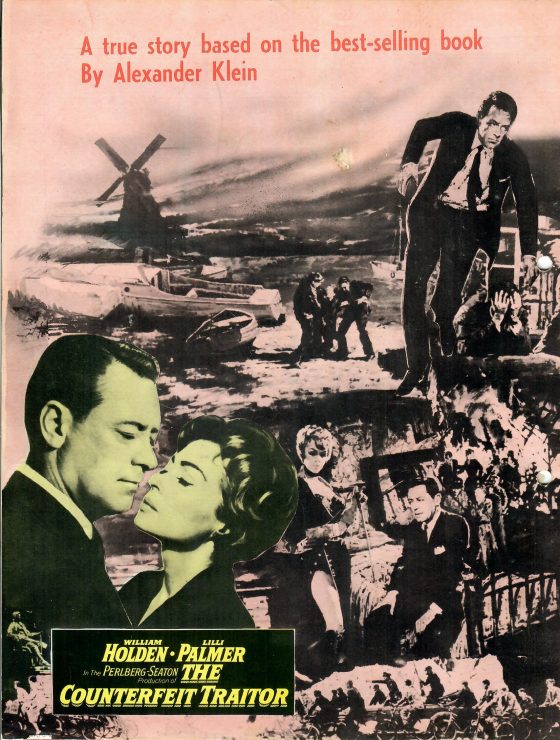

In this film William Holden plays master spy Eric Erickson whose stranger than fiction adventures led him to be labelled ‘the man who did business with Himmler’

It is a very good William Holden performances in The Counterfeit Traitor where he plays an American born Swedish businessman who agrees to spy for British Intelligence

They made him an offer he couldn’t refuse after Holden is put on a list of undesirable businessmen who are doing trade deals with the Germans. Holden’s character is American born, but had become a Swedish subject after deciding he would be working and living out of Stockholm. By agreeing to spy William Holden will get cleared after the Allies win the war we assume.

Eric Erickson ( played by William Holden ) proves to be quite useful to the Allies giving them all kinds of information about where Nazi war production is so it can be targeted by Allied bombing. Of course each trip from Sweden to Germany brings new risks as the Gestapo crack down on traitors.

One of his contacts is Lilli Palmer, a prominent society woman with whom he begins an affair. Lili Palmer herself was a refugee from Nazi Germany so she was well able to understand and get into the part and the era

Hugh Griffith is very good as the cynical British agent who is Erickson’s contact. Also in there was Werner Peters the German actor who played a really terrific variety of Nazi types throughout the Sixties and later. Here he is very suspicious of Erickson from the outset.

The Counterfeit Traitor is a fine espionage film and definitely in the top ten of William Holden’s performances.

Lili Palmer

Actress Lilli Palmer fled Nazi Germany after her theater contracts were revoked and she was branded a “non-Aryan” and narrowly escaped arrest. She first fled to Paris and then to London, where she acted in her first film and married Rex Harrison in 1943. Following Harrison to Hollywood, she made a name for herself and was immortalized with a star on the “Walk of Fame.” In 1948, they moved to New York, where Palmer shifted from films to theatre. Palmer returned to Germany in 1953 to make several award-winning films. She later turned her hand to painting, writing, and hosting a talk show with Dick Cavett.

“There was never any doubt in my mind that I would become an actress,” Lilli Palmer wrote in her autobiography. Defying the wish of her physician father Alfred Peiser (d. 1934) that she study medicine, Palmer fulfilled her own prophecy by following instead in the footsteps of her mother, actor Rose Lissmann. Palmer became not only a prominent actor in numerous successful plays, films and television programs, but also a painter and an author of both fiction and non-fiction.

Early Life and Family

Lilli Peiser was the middle daughter born to an assimilated Jewish family in Posen, Germany (now Poznan, Poland) on May 24, 1914. She had two sisters, Irene (?) and Hilde (b. 1921). As she later wrote in her memoirs, she was reminded in her childhood only once a year that she was Jewish, when she was discouraged from participating in the school Christmas play. But she acted in many other performances at the Open Air School in Berlin-Grunewald—where she already took the stage name of Palmer, who was a friend and colleague of her mother—and secured a contract with the well-reputed Darmstadt State Theater upon graduation from drama school. After Hitler came to power in 1933 Palmer soon faced grave reminders of her Jewish heritage. Her recently negotiated two-year contract with the Frankfurt Playhouse was cancelled. Branded a “non-Aryan” she came near to being arrested by local Nazi authorities during a performance in Darmstadt. After a harrowing opening before rows of Storm Troopers, Palmer was spared at the last minute when they learned of the World War I Iron Cross medal earned by her father, who was at this point serving as chief surgeon at Berlin’s largest Jewish hospital.

Acting in Exile: London, Paris, Hollywood, Broadway

These events forced Palmer into exile, the first year of which she spent in Paris. Hindered by linguistic, cultural and bureaucratic barriers, Palmer and her sister Irene barely scraped by with performances at the Moulin Rouge and at nightclubs. But Palmer was able to establish connections which led to a screen test in London, where she landed a part in her first film, Crime Unlimited (1935). Soon she signed a contract with the Gaumont-British film company and after various hurdles in obtaining work permits in England she was eventually granted a permanent permit, lending some security to her life in exile.

In London Lili Palmer met one of her greatest influences, Elsa Schreiber, considered by many to be a mediocre actor but a marvelous acting teacher. Schreiber taught her the subtleties of refining a character and a script—a method which later brought Palmer into conflict with some of her directors—and helped Palmer with her roles for years to come.

Lili Palmer married actor and frequent co-star Rex Harrison (1908–1990) in 1943 and had their son, Carey, in 1944. The family narrowly survived air-raid bombings during wartime in England. They moved to Hollywood in November 1945 for Harrison’s role in Anna and the King of Siam. Palmer quickly resumed her career with the lead role opposite Gary Cooper in Cloak and Dagger, amid heated disputes with émigré director Fritz Lang (1890–1976) which nearly caused her to withdraw from filming. With such films asBody and Soul (1947), My Girl Tisa (1948) and No Minor Vices (1948), Palmer continued to make a name for herself in Hollywood, where she was eventually immortalized with a star on the “Walk of Fame.”

After a scandal involving the 1948 suicide of Harrison’s lover, actor Carole Landis, Palmer and Harrison moved to New York and sought work on Broadway. Palmer quickly revived her reputation with such successes asGeorge Bernard Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra (1949) and, starring with Harrison, John van Druten’s Bell, Book and Candle (1950). Harrison and Palmer divorced in 1957, and Palmer married Argentine movie star and writer Carlos Thompson (1923–1990) the following year.

When Palmer returned to Germany to make the film Fireworks (1953) she realized her German had grown rusty during her prolonged absence: she did not know the technical terms for making movies in German. In addition, she struggled with being back in her home country for the first time since 1933 and was haunted by the question “What did a former Nazi party member look like today?” (Change Lobsters—and Dance 257). Palmer made several more German films, including Devil in Silk (1956), Anastasia: The Czar’s Last Daughter (1956), Between Time and Eternity (1956) and Tempestuous Love (1957). She won the Berlin Film Festival’s best actress award for the drama Devil in Silk in 1956, three years after winning the Venice Film Festival’s Volpi Cup for The Four Poster.

Working with New Media: Painting, Television, and Writing

Palmer once noted that she wanted to be remembered simply as a person who had led an interesting life (Huebner, 235). The varied activities undertaken in the last few decades of her life only increased her chances of this commemoration. She began to pursue more seriously her hobby of painting, even receiving advice and encouragement from the renowned painter Oskar Kokoschka. An exhibit at London’s Tooth Gallery showcased twenty-five of Palmer’s paintings, most of which were sold on the spot. Palmer also displayed her writing talents in a witty and best-selling autobiography, Change Lobsters—and Dance, as well as four novels and a short-story collection.

Gradually decelerating her movie-making, Palmer began work in another popular medium: television. In 1972 she acted in a German comedy, “A Woman Remains a Woman” (Eine Frau bleibt eine Frau), for which she won a Golden Camera award. She also did much of the show’s writing under the pseudonym of her grandfather’s name, Herrmann Lissmann. Palmer soon became a familiar television personality, hosting a talk show with Dick Cavett in 1979 and conducting a candid interview with German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt in 1982. In 1987 she received a posthumous Golden Globe nomination for her supporting part in the American mini-series Peter the Great. Despite her fame in many diverse areas, resulting in occasional mud-slinging from the press, Palmer always made time for her fans, whose books she happily autographed.

In May 1985, as she worked fervently on her final book, When the Nightbird Cries, Palmer hid her diagnosis of abdominal cancer from friends and family. She died in Carlos Thompson’s arms in Los Angeles on January 27, 1986, having left her mark as an accomplished actor of stage and screen, painter, and writer