Late in 1947, Peter Ellenshaw’s work caught the attention of an Art Director for the Walt Disney Studios. Disney was in the pre-planning stages of his very first live-action film, Treasure Island (1950), which would be produced in the United Kingdom.

Thus began a professional collaboration and friendship with Walt Disney that would span over 30 years and 34 films. Ellenshaw supplied mattes for the next three remaining Disney films made in Great Britain (The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men, The Sword and the Rose, and Rob Roy) and soon relocated to California in 1953, where he did matte work on Disney’s first U.S.-produced live-action feature film, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

Ellenshaw’s matte paintings saved Walt the cost of expensive location trips and elaborate settings. When Davy Crockett headed for 19th century Washington, D.C. or Mary Poppins flew over the rooftops of London or Robin Hood stormed the castle or Paul Revere rode down the streets of 18th Century Boston—that was all the magic of Peter Ellenshaw.

More than 10 years after his work on Treasure Island, Peter won his own Academy Award for his work on Mary Poppins (1964). In all, he was involved in 34 films for Walt Disney Productions between 1947 and 1979.

As a matte artist, the wide range of Ellenshaw’s contributions can be found in Johnny Tremain, Old Yeller, Zorro, The Great Locomotive Chase, Swiss Family Robinson, The Absent Minded Professor, Blackbeard’s Ghost, and The Love Bug, to name just a handful of films that featured his artistic talents.

In addition, Peter contributed to the special photographic effects of Darby O’Gill and the Little People, served as production designer on Island at the Top of the World, and as art director on Bedknobs and Broomsticks and The Black Hole.

One of Ellenshaw’s first Disney projects upon his arrival at the Studio was to create a rendering for Walt’s newest project, Disneyland. Ellenshaw went to work painting an aerial view of the proposed park on a 4-foot by 8-foot piece of storyboard. The painting was then used by Walt Disney to help introduce television audiences to his new project as well as attracting potential sponsors.

Ellenshaw contributed his artistic touch directly to many of the early Tomorrowland attractions at the new theme park, including the first Circarama show “A Tour of the West” sponsored by American Motors, TWA’s Rocket Ship to the Moon and Space Station X-1 that showed a “satellite view of America from 50 miles up.” In 1993, Peter Ellenshaw was named a Disney Legend.

In his spare time, Peter primarily painted sailing ships and, later, seascapes. It was Walt Disney who introduced Peter to the beauty of the desert. When Walt was in the hospital shortly before his death, Peter painted for him a desert vista featuring the smoke tree that Walt loved.

The tree had a light, feathery appearance resembling smoke, and was prominent at Walt’s vacation home in Palm Springs, the Smoke Tree Ranch.

Walt’s secretary, Tommie Wilck, took it to the hospital on December 10, 1966 (five days before Walt’s death) and told Peter how Walt proudly told the hospital staff that “one of his boys” had painted it especially for him.

Here are some excerpts from an interview with Peter in 1997with Jim Korkis

Jim Korkis: How did you get an offer to work for Disney?

Peter Ellenshaw: I got a call from an art director, Tom Morahan, who was working on a film for Disney. The exciting thing was I hadn’t thought of working for Disney. He was an animator. But when my chance came, I grabbed it. I said, “Wow, even if I only get to do one painting for Disney, I’ve got to do it.” It turned out the film was “Treasure Island.” It was the first time I had painted ships for a film and I think it was Walt’s first experience with mattes.

I had been told it was probably not going to be worth my time because they only needed a few mattes but I ended up doing 40 or more mattes in that film. On The Sword and the Rose, I painted 62 mattes in 27 weeks. What was I thinking?

J.K.: Of course, Walt told a quite different story of how you met.

P.E.: That story has haunted me for years. I am sure Walt was trying to joke but many of the men in the room didn’t realize that fact.

Walt came into the dailies one day and everyone was sitting there and he said, “You know how I met Peter? I was walking around Trafalgar Square and there was this guy doing some drawings on the pavement. He was painting a loaf of bread on the sidewalk. He’d written ‘Easy to draw, hard to earn.’ And I thought the drawing was pretty good so I said, ‘They’re pretty good. How would you like to come to America and work for me?’ and he said, ‘Yes, I would, governor!’ and that was Peter!”

And what bothers me to this day is that some of those guys believed him! It is a complete myth but Walt loved to tell stories and to have fun so I have seen it printed as if it were absolutely the truth.

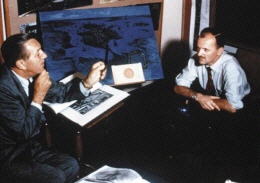

J.K.: How did you get assigned to do that huge painting of Disneyland?

P.E.: Walt came in one morning. I’d only been there a few days in Burbank. He came in and said, “I want you to paint a picture. We’ve got the plans of Disneyland. If you could do a perspective, aerial drawing of it, that’s what I need.” I got a storyboard. We had big storyboards there about four feet by eight feet and I thought I’d paint on that. We didn’t have the facilities that you have now. I set this thing up and started painting it.

After I had finished, he came in and said, “I am coming in tomorrow with some people from Look magazine. I am coming in and I would like you to be here because I’d like you to be included. We’ll be here at 8:00 am.” (It appears as a two page full color spread in Look magazine November 2, 1954.)

J.K.: For a long while, I thought you had done two versions because I remember seeing on television the daylight version and also a nighttime version.

P.E.: I used some luminescent paint so under fluorescent light, it would show what the park would look like at night. Walt did do that with the painting on one of the television shows going from day to night and it was very effective. He used that same image on postcards. He sold thousands and thousands of postcards and I never got a penny of that! (laughs) It was used on souvenir books. All over the place. They later found it in a shed at the Disney Studio somewhere and it was restored and exhibited at the Disney Gallery at Disneyland.

J.K.: Actually, your work on “Davy Crockett” led to an interesting request from Walt, didn’t it?

P.E. Walt came in one day. We were at the rushes and that was the place to be because the boss would be there and he gives great ideas. He’d tap me on the shoulder because I’d be in the row in front of him. Boy, I felt good. “Oh, the boss touched me and said, ‘Hello’.” I was in heaven. He didn’t do that with everybody. I really felt privileged.

He tapped me on the shoulder that morning. “My wife’s a fan of yours.” But he said it very begrudgingly. “She likes that Davy Crockett cabin painting and would like a copy. Talk to me later.” Copying a picture, especially your own and trying to make it the same is a fool’s thing. When you try and do it again, you try to improve it stupidly. You can’t improve it. You make it dead. You lose the life of it.

When I had finished the copy, it looked nice enough but it didn’t have that touch. She was sharp enough to see it. I took it to them at their home. “Oh, very nice,” she said. “Very nice” is always a dangerous one. She took the painting and later I heard that she had sent it down to Disneyland and asked for the one they were displaying, the original I had done for the television show. So she had the copy hang down at Disneyland and she had the original. Eventually she got the copy as well. I went to her house recently to photograph it for my book.

J.K.: Mary Poppins remains one of the best beloved films yet most people probably don’t know about a special voice you provided.

P.E.: In those days, the wonderful part of the whole place was that you were called often to do all sorts of odd things like voiceover work. Now it is done by professionals. Now it is not allowed for someone like me to just drop down and do it. In those days, it was fine.

I am also something else in the film. I am an actor in it. I am the hand that goes into draw when they say “there’s a road down through…” when Bert is sketching.

J.K.: And of course, you also get credit for the “Step In Time” number in Mary Poppins.

P.E.: Bill Walsh who co-produced Mary Poppins came in one day and asked me if I knew any vulgar songs. That wasn’t something obscene but something common. Something low-life chimney sweeps might sing. Well, I had gone on a pub crawl and my friend and I would get everyone up in the different pubs we went to and have them sing and dance to an English song called “Knees Up, Mother Brown.”

I showed Bill and he immediately brought in Walt and storyman Don DaGradi, who was one of the best storymen ever at Disney. We danced across the room and back with our arms linked and our knees up very high. It seemed very strenuous for Walt. We didn’t know at the time he might be sick. Walt said to bring in the Sherman Brothers who were writing the music and I had to do it all over again.

Of course, they couldn’t use the actual song so they came up with another song that was similar. I think it was a little too elegant in the final film. It really is much more fun when it is vulgar.

J.K.: Whatever happened to all these great matte paintings that you did?

P.E.: We had to have glass and it was a difficult time to get the glass when I would need another one the next day. We sent those matte paintings down to the painters and they would wash it, clean it all off, so we had another one for the next day.

If I had been allowed to keep them which I wouldn’t have been, I would be a much richer person now. (laughs) They were painted on glass with oil… later acrylic… and then they were scraped off almost immediately so we could reuse the glass for another painting. I’ve seen a few that weren’t scraped and the paint didn’t survive well. It yellowed and chipped. It was like the cels for the animation. It was just part of the process.

It wasn’t meant to survive beyond being filmed. Remember that to judge a matte painting you have to stand back where the camera is and make sure not to give it too much detail, just enough to fool the eye. Too much finish on it and it becomes static. It doesn’t look quite real. One time, Walt was looking at one of my mattes and said, “Looks like a painting” and all the guys started laughing thinking it was a joke but it wasn’t. Walt was trying to tell me to put less into it, not in terms of quality, but detail so that it was the illusion of being real.

J.K.: What was Walt Disney really like?

P.E.: What was Walt Disney like? That’s what we’d all like to know, isn’t it? Walt was the only person who was not an artist who could talk to you like an artist. The only problem you would have had with Walt was if you were not as enthusiastic about a project as he was. I would remember him coming by and talking to me about something and would get me all stirred up with enthusiasm and I would start work on the project. It wasn’t a false enthusiasm. He really believed it could be done and he was able to make you believe it.

Great man. Wonderful man. Loved him. Missed him. Missed him terribly. Missed him so much that I’d wake up in the middle of the night and wonder why I was weeping. It was because I’d lost him. It was wonderful knowing him.

I was just one of the people who knew Walt just from live action. I’m not boasting about that. I’m very humble about that. I used to sit around with these men who had worked with him for so many years in animation and we’d ask, “What makes this ordinary man so extraordinary?” Because he seems so normal. He seems so common in his thinking. He has no taste. Suddenly, you realize he has exquisite taste. He had a certain way of thinking and looking at problems from over there.

We were all looking at it the same way from the common view and he’d say something and we thought he hadn’t been listening to what we were saying at all. Actually, he had seen it from another view. In meetings, I felt obligated to come up with something so I’d come up with some stupid thing. “Peter, what are you talking about?” he’d say and lift that eyebrow. What an extraordinary man! Just an ordinary, humble, gentle tyrant.

J.K.: Any final thoughts you’d like to share?

P.E.: Extraordinary things happen in your life if you want them to.

BELOW – A much later film and not one of Peter Ellenshaws but it shows what a wonderful technique matte painting in films was and is, and the sheer scale and illusion that it can add. The film was ‘Predator’ which was released in 1987 – and which did extremely well at the Box Office

The Pictures below are from an excellent web site with loads of details on this technique – I thorouhly recommend you visit :-

http://www.nzpetesmatteshot.blogspot.co.nz/2010/07/creature-feature-special-visual-effects.html

This is one of my own very favourite web sites

ABOVE – The actual Film shot – and BELOW with the bottom half a matte painting

ABOVE – This is what we, the audience, saw

ABOVE – The Bottom Matte

The Bottom Matte Painted on Glass ABOVE ready to be filmed when lined up with the top picture

Place your comment