I know that these films were made very much ‘on the cheap’ but I have a liking for them. Ford Beebe Directed and I have seen an article somewhere where Johnny Sheffield gave his thoughts on Ford Beebe – he rated him highly and was impressed by his ability to be able to see the film in his head as he shot it – stating that he almost edited the film as he went on- so he shot the scenes and usually printed what he got in one take. Very efficient no doubt.

These were simple little films but enjoyable for us young lads at the time – I must admit that I haven’t seen a Bomba film for a long while

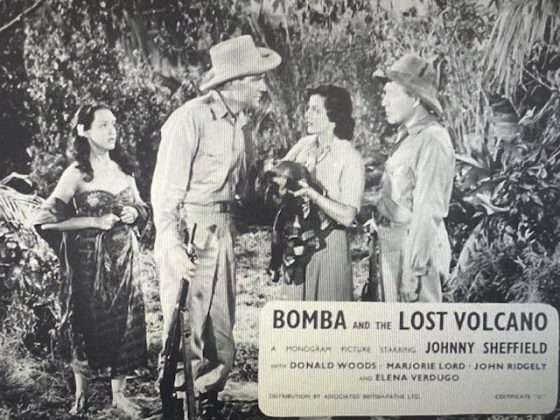

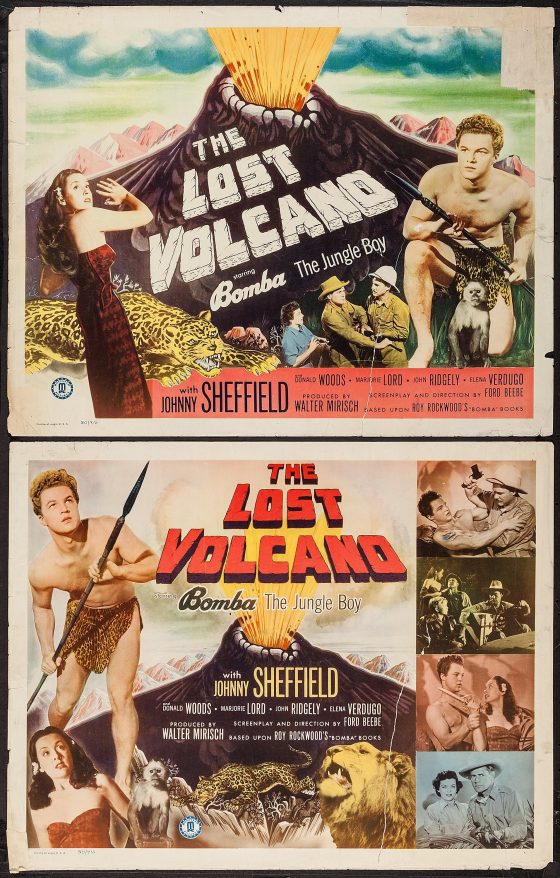

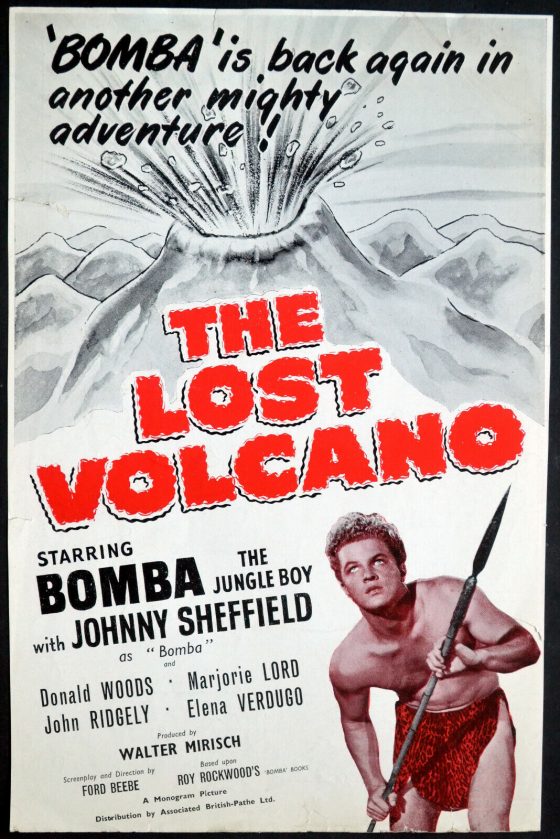

Bomba and The Lost Volcano – This is not a film that I have seen but seen some of the others in the series

Bomba

Bomba and The Lost Volcano

Bomba and The Lost Volcano

Bomba and The Lost Volcano

Bomba and The Lost Volcano

Bomba and The Lost Volcano – even a Colour still from the film

I have copied this very interesting interview with Johnny Sheffield BELOW – I must admit that reading it, he does come over as an intelligent and perceptive person – and even in his very young days, he seemd to get an angle on events :-

From a Johnny Sheffield during our interview, in the garden of his Chula Vista home, in 2000

Johnny Sheffield was the son of British-born character actor Reginald Sheffield (1901-1958). Born in Pasadena, California, in 1931, Mr. Sheffield still resided in California when I met him in the summer of 2000 on a terribly hot Sunday afternoon, but the shade, a few cold drinks, the nearby pool and most of all the company of this generous, intelligent, and humorous man made it all the more worthwhile and interesting. He still had the charisma he had when he was a child star, in the days when he influenced several generations of youngsters while exploring and surviving the dangers of the jungle.

Mr. Sheffield, how do you remember your father, a child star who became a stage and screen character actor and who started his screen career in 1913 with “Lt. Pie’s Love Story”?

Well, he never attained great fame, but he was a highly respected character actor. He started on the London stage and came over to the United States in a company with George Arliss [1868-1946, one of the most popular and distinguished stage and screen actors of his era and Academy Award-winning actor in 1930 for his role in “Disraeli”]. I was brought up in a theatrical family and was always around theatrical people, so learning lines was just second nature. To me, there was nothing difficult about it. There’s only some technique involved in learning. When I was seven, my father went over my lines with me, but normally children don’t have any problems with memory or fantasy. As a child, he’d take me out to the theatre. He’d talk to the stage manager and ask permission for us to use the theatre. It would be dark, except for the stage lamp, I would get up on the stage by the stage lamp, and he’d speak to me all over the theater, on the balcony, down underneath the balcony, ask me questions, teaching me to speak so I could be heard without shouting. I guess they teach those things in acting schools, but everything I did, also on the screen, wasn’t difficult for me as a child, because at the studios, we also had the best writers, costume designers, set directors,… All I had to do was step into this fantasy, which is very easy for a child. The children and the young people who watched the Tarzan movies couldn’t wait to get out of the theater and get the ropes over the trees, do the swings, have the fun and play Tarzan themselves. To become Boy when I was a child, was very rewarding to me. I was Boy, and I later on was Bomba.

So not only learning your lines but also acting and the whole concept of making movies was like a second nature to you?

When I was young, I never made a conscious choice like what I wanted to do—how can you, at that age. It was all very natural to me. It’s like a carpenter who teaches his son to be a carpenter. The son is offered the opportunity to learn a trade. I think all fathers are that way; they’re interested that their children know how to take care of themselves one way or another, through education, a trade or some other activity. Many fathers pass on what they have learned to do to their children. Today the young people are terribly caught up in the culture of setting goals and fulfilling them in their lives, which may be very good, although it may present a lot of pressure on children to work hard to obtain those goals. There’s certainly a time in your life when that’s important, but at five years old, I didn’t set a goal to have the largest legitimate stage part ever written and to be on Broadway two years later, starring in “On Borrowed Time,” playing the role of Pud. It just happened. My father taught me his business, and he was very good at it. He trained me and placed me in a position where I could take advantage of the opportunities. Nor did I make a goal to be a star at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer by the time when I was nine, playing with Olympic and world champion Johnny Weissmuller. So all of this just happened for me, and that’s how I got in the acting business.

Did you realize as a child what was happening? The stardom, the attention, the privileged world you lived in, was it something that you took for granted?

Oh no, I didn’t know the effects of that at all. It took me about fifty years to look back and try to understand what happened to me as a child when I became famous in the first few years of my life. I was the youngest in my classroom at MGM. Mickey Rooney sat right here, Judy Garland sat right up there, there were many of us, and some had difficulties all their lives, handling what was made to be special. For me, it was a natural day when they said, ‘Go play with the lions or the elephants’—or being driven in your own car, travelling across the country in your own train, that was routine for me. So when others make something special out of that while you’re still a child, you don’t understand that. Even today, people still come up to me and say, ‘Aren’t you Johnny Sheffield? Tarzan Junior?’ There’s still something recognizable because it happens wherever I go. It has been that way all of my life, and I have been out of this business for such a long time now. So it takes a long time to understand what that influence does to you. The abnormal attention you get is attention you do not choose to have. It happens in a normal course if you learn how to be a carpenter, but then, people don’t stop you in the street and ask, ‘You remember that house you built in 1942 at 221 South Bundy Drive? How did you put the wall into the bathroom? How did you pound the nail in the third stud over in the bathroom?’ They don’t do that, but if you’re a motion picture star, they do ask about this or that movie you made fifty, sixty years ago. And yet, when making that film, you come in, you read your script, you learn your lines, and you shoot it. You pound the nail. Later on, you never see that nail again, except maybe on the screen. But it is made to be so special; when you’re very young, you don’t understand that, so you’re set apart.

What about the fans who wanted your attention? How did you cope with that as a youngster?

The fans, or those who are interested, become the enemy unless you decide that you want all that attention. It takes a certain amount of maturity to make a decision like that, but when it just comes, there’s a lot of pressure from the fans. It had quite an effect on the life of the young people that I have seen in this business. When I got to the age where I would be making decisions about my life and what I was going to do, I was getting out of the business, that’s for sure. I didn’t need that, even though I loved the motion picture industry, the people in it, and all the fun we had. But there was the pressure from the fans, or from that pain from being set apart because of that particular thing that you do—which doesn’t take any more talent than being a very good carpenter, for example, in his field. You understand the analogy I am trying to make? It is a very interesting medium that is really making something out of the people who are in it, beyond what a child would even begin to understand or even make a decision. So I was retreating in getting away.

So it was by choice.

Well, you got to learn to hit first or decide if you want to be there at all. So that’s the reason I didn’t continue in the motion picture business. Even though I could have made a lot of other pictures at that time, but I never turned back, and I have had a wonderful life so far. So I never regretted that decision. There’s an old saying, ‘When one door closes, another door opens.’ That’s the way my life has been. When I was too big to play Boy, that door closed. Then producer Walter Mirisch had the idea for the Bomba series, and when that door closed, I was twenty-four in 1955—pretty old to play Bomba. I then said, ‘Well, I’m out of it.’ But my father wanted me to do one last thing, a series for television because that was a terrific medium and we could do something very entertaining for the young people, called “Bantu, The Zebra Boy.” Both my father and I knew about making pictures, so we made the pilot, but we didn’t know about selling it to the sponsors and the agents who were in the business. That was something we didn’t really know about, and we turned it over to some agents to sell it. But it never sold, and it has been sitting over here in my vault for nearly forty-five years.

It’s still there?

I know some people on the Internet and I told them, ‘I’d like to sell a Bantu collectors package.’ And they said, ‘Well, sure!’ So I offered an authenticated copy of the original TV pilot that was unsold and unexhibited—a collector’s item for those who have the Tarzan and the Bomba pictures, and if they could have one that has never been seen, I thought that would be unique. The package included a certificate of authenticity, a couple of stills, also of Johnny Weissmuller and myself. I thought, if I get one or two replies, it would be interesting. I think we got about twenty. The first one came from Brazil [laughs]. I also took some of those collectors kits with me to film festivals—I went back to motion picture-related things after fifty years—and they were very well received.

And what about now? Are you in any way involved in the motion picture industry?

I still attend events in Hollywood. Mostly they are charitable events to raise money for the Hollywood Motion Picture Relief Fund or those kinds of things. The first one I went to, I saw Maureen O’Sullivan [also a former classmate of Vivien Leigh and the mother of Mia Farrow] was there too. I hadn’t seen her for maybe forty or forty-five years. I was talking to Milton Berle, she tapped me on the shoulder and said, ‘Hello, Boy, how are you? How have you been?!’ Her voice hadn’t changed a bit. It was just like when I was a kid. You can be away from each other for a long time, and when you come back, you just pick up wherever you were. There was a lot of chemistry with all of us involved in the Tarzan films; we all loved each other, we were like a family. Johnny, though, wanted at one time to do something else, but it never worked out. Later on, he played Jungle Jim, but the tragedy with Johnny was that his business manager lost all his money—too bad, of course, for a guy who shouldn’t have had any financial worries at all. Maureen O’Sullivan had left the series because she wanted to play more serious roles. When I saw her again at that event, she said, ‘You know, I have come to reconcile myself with the Tarzan films, and as it turned out, I was very fortunate. I was a working actress all my life.’ Up until her seventies, she was still working. She told me that her appearances with Johnny Weissmuller in the Tarzan films, along with being a part of that series and the fame because of it—it is a classic series now—it is what she will always be remembered for, not for any other screen or stage role she played. I knew at the time it was something that would be going on for a very long time after I was out of it.

What happened to all of you after she had left the series?

When Maureen O’Sullivan left the series [after her third Tarzan film, “Tarzan’s New York Adventure,” 1942]. She was replaced by Brenda Joyce [first of her five Tarzan films was “Tarzan and the Amazons,” 1945]. She was very well accepted, but we don’t make any comparisons. People always like to make comparisons, like, ‘There will never be another Tarzan like Johnny Weissmuller,’ or ‘There will never be another Jane beyond Maureen O’Sullivan.’ There have been other Tarzans and Tarzan films, but I don’t think there has ever been another family situation like we had with Tarzan, Jane, and Boy. Brenda Joyce is about eighty-five right now; I tried to get in touch with her again, and wrote her some time ago when she had moved to Monterey, but I never got any answer from her. As far as I was concerned, she was a fine Jane, just as Maureen O’Sullivan was fine in portraying her role of Jane. But I don’t compare them. It’s like asking me what’s my favourite film; I wouldn’t know and if I would be forced to give a title, I would probably say “Tarzan Finds a Son!” which was my first film, that was my introduction to film when I made the change from the legitimate stage to the mechanics of working with a camera and film.

How do you look back now to your Tarzan era?

After all those years, I felt I had lost a lot of my life, withdrawing from having so much success and fame through Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and this wonderful idea from [author and Tarzan creator] Edgar Rice Borroughs [1875-1950] as I stepped into it at a very young age. If you’re in show business at age thirteen or fourteen and you tell everybody about what you’re doing, you’re a show-off. And if you don’t say anything, you’re conceited. So there’s no relationship you can have, based on being a star at MGM or having your own series in motion pictures. There’s no common ground; the only common ground I had, was intellectually and in sports, on the football field or something. So I had lost a lot, I couldn’t talk about it. Back then, I couldn’t say, ‘I was in the commissary at MGM and had lunch with Wallace Beery.’ You can that now because people are interested, but not back then. You can understand there’s a conflict there. So later on I thought, ‘I am finally going to accept an invitation to attend film festivals and confront what to me was the enemy. The first time, when I hadn’t made any public appearances in years, I had a very nice time talking to fans and admirers. I reconciled myself with the fans who turned out to be normal people, not crazies. Some were school teachers or film collectors, you know. The main thing they wanted to say, was just to thank us for the good times they remember as children, going to the movies back then.

What kind of contract did you have at MGM?

When making the Tarzan films at MGM, I never had a contract of more than one picture. I had a picture-to-picture deal. I was not in the system like many of the younger people who went to dance class and took singing lessons. I was either making a picture or I was in the public school system. When I was making a picture, I was in the school system I described. When we weren’t making a picture, before and after—when I was still at the studio—I was in the studio school. Miss MacDonald was our teacher; she taught the whole class. A lot of people who were under contract, had regular schedules of training and teaching. You know, it takes a long time to find out what it’s like to be brought up and spend your formative years in a position of fame which is what MGM did with their stars. You could go anywhere in the world, and they would recognize you. To me, that’s fame. To work with an undefeated Olympic champion—those people don’t think like other people think. I was brought up from eight years old till about fourteen in that environment with Johnny Weissmuller. My father recognized the advantages and the importance of that, and he let me go with Johnny all the time. I’d go to swimming or diving events with him and his other champion friends. Pretty soon, they’d start thinking you were a champion too! I also had the best teacher in the world; he learned me how to swim. Johnny Weissmuller was always encouraging, he didn’t want to do anything with any negative attitude at all, he wouldn’t be around those kinds of people. Champions don’t have time for any of that. They’re always upbeat, positive, happy, joking, and they got a little clock ticking inside. I also got that same kind of attitude, that’s where I got it. In your life, there are bad things and good things going on all the time. It’s up to you to decide how much time you want to spend on both—you certainly shouldn’t spend too much time on your problems.

Is there any difference between child roles back then and now?

Children now have more access to screen roles than we did. There’s no studio system now, but the total number of roles has increased. There’s more opportunity—in everything. People sometimes say, ‘This is the worst time to live.’ My God, I can’t believe what they’re saying, this is the best time you could possibly ever live. There are more opportunities, there’s more access, more things to do. There’s a downside too, of course; society has problems, but we always had that. There are a lot of people watching too much television and not living enough life themselves. There’s also too much reportage of what’s going on everywhere, so people lose focus on things. It’s gotten to the point where if somebody falls down in the street out here, I might be more concerned about the Somalians than going out and make sure this guy gets picked up and is taken care of—or because of some news report, we think, ‘No, we can’t touch him or we’ll be sued.’ We lose track of human values of what we should be doing in this life. There’s a lot of distraction. People are agonizing over, let’s say, something that’s going on in Germany or in Pakistan, but if everybody makes sure everything is okay where they are, the whole world would be fine. When I retired from acting at age twenty-four, I didn’t really like the entertainment business anymore because it took the audience away from what they ought to be doing—it sounds funny, but somebody who is looking for distraction by watching TV twenty-four hours a day is sick. And if I am the guy on the TV screen, I don’t like to be part of that, just like I couldn’t be a bartender selling alcohol to a drunk. That’s the reason why I got involved in agriculture and became a farmer in Arizona: you can’t hurt anybody or can’t get hurt too badly yourself in agriculture. You just put the seed in the ground, God gives us the light and the water, the plant is going to grow, and you can feed people. Then I got involved in construction and had my own construction company. I like to build things, put things together, then walk away from it, and you haven’t really hurt anybody. I still build, I can’t stop—it’s like the guy on the corner, he has five apples for sale at five cents a piece, a man approaches him and says, ‘Here’s twenty-five cents. I’ll take them all.’ Now he sold them all, what would he do? He wouldn’t have anything to do! [Laughs.]

Has your life in films been more or less rewarding than your life outside motion pictures?

Well… what is rewarding? Staying alive, which is having your needs met, and being able to experience life. Today most people talk about what’s rewarding, and they mean material rewards. It’s rewarding to me that through the years I’ve always done something for somebody else if I could do it, although it hasn’t always been easy. But I do the best I can. That is rewarding because the command is to love one another and you can’t do that by yourself without being with others. You got to have an intercourse with your fellow human being. Just like there are certain physical laws in this universe, I think there are certain spiritual laws in this universe as well. I can stand on top of that roof and deny the existence of what we put together into a law of gravity—you even don’t need to have a law for it; gravity exists. I can be against that and not in agreement with it, but as soon as I step of that building, I’m going down, whether I agree with it or not. I think the spiritual laws are the same way. You can be in agreement or disagreement, it doesn’t matter. If you’re a lying bag of shit, as we say in America, or a thief or a drunk, you’ll go down. Somewhere you’ll be going against some spiritual laws, and they will take you down. Various religions tell us and point us in directions of a higher plane of life, of living. That is the total reward. What we have to strive for is get in touch with these spiritual laws, try and follow those. So it doesn’t really matter what you’re doing: if you do it in a certain way and try to follow certain principles, you can have a full and happy life.

That is the end of the interview – interesting and it gives us an insight into the life a child actor had in those days – an insight from his own point of view I should add !

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on to that Topic: filmsofthefifties.com/bomba-and-the-lost-volcano/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here to that Topic: filmsofthefifties.com/bomba-and-the-lost-volcano/ […]