Ronnie Ronalde has died a day or so ago – a name I remember so well from the radio days here in England in the early fifties. However I forgot that he whistled the soundtrack for Innocent Sinners in 1958 – a British film not really much known these days. I must search it out because apparently it is a charming film of its time – and it is adapted from a novel by Rumer Godden – featured on this Blog a while ago when we covered another of her works – Black Narcissus and The River.

And what about Ronnie Ronalde – The Voice of Variety AS HE WAS CALLED..

In the 40 s and 50 s he was a headliner, and broke box office records all over the world – he was a big name in the UK, US, Australasia, Scandinavia, Africa, South America and Europe.

Such was his success in the US in the 1950s, he was seen as serious competition to Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby, and others such as Richard Tauber and Josef Locke.

Ronalde had his own BBC Radio Show from 1949 called The Voice of Variety. During this series, the volume of Ronalde’s fan mail caused a problem for the BBC. The Voice of Variety News fan publication had a print of 55,000 copies twice yearly, and fan clubs during this era existed all across the UK. Thames TV also presented a weekly show titled Meet Ronnie Ronalde.

In 1949 Ronalde filled Radio City Music Hall in New York City (with capacity of over six thousand) every night for ten weeks. He was at that time the most frequent UK artiste to ever perform there (over a thousand times).

During the same period he filled a 25,000 capacity venue in Toronto Canada for a fortnight.

Ronnie Ronalde whistled the theme to Innocent Sinners.

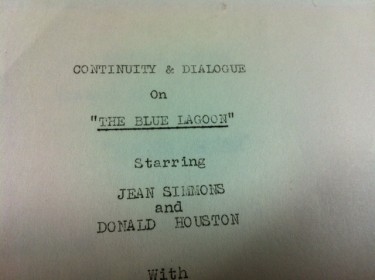

Gentle children’s drama based on the novel An Episode of Sparrows by Rumer Godden following a Cockney girl’s efforts to brighten her drab life by cultivating a bomb-site garden. Director Philip Leacock was an adept hand at capturing youthful emotions and had earlier done so on films including The Kidnapper’s (1953) and The Spanish Gardener (1955). Characteristically of the director, it’s a sensitive and well acted drama.

It is set in London during the period of post-war austerity. A 13-year-old girl, Lovejoy Mason (June Archer) lives with guardian parents whilst her mother Bertha (Vanda Godsell) treads the boards at the coastal holiday resorts. When the girl comes into possession of a packet of cornflower seeds she decides to make something beautiful out and creates a small garden in a bombed-out section of London. To tend her garden Lovejoy requires two-shillings for some garden tools and resorts to singing in the street – where she comes to the attention of terminally-ill resident Olivia Chesney (Flora Robson). She eventually gets the money she needs by robbing the collection box at a nearby bomb-damaged Roman Catholic church

A group of street urchins led by street-smart Tip Malone destroy Lovejoy’s garden and the young sparrow is forced to scour London in search of a new plot. Tip feels remorse for vandalising Lovejoy’s creation and offers to help her create a better garden in the grounds of the ruined Catholic church – providing she repays the money stolen from the collection box. Meanwhile, Lovejoy’s guardian’s, dreamer Mr Vincent (David Kossoff) and his wife Emma (Barbara Mullen), have troubles of their own with a restaurant that is failing and when news reaches them that Lovejoy’s mother has married and eloped to Canada the couple no longer have the funds to care of their young ward.

Lovejoy and Tip are arrested by the police for stealing from a communal garden, and together with her mother moving away, the young teenager is taken into care. The one sympathetic figure transpires to be golden-hearted spinster Olivia Chesney, who having overseen Lovejoy’s predicament, calls on her solicitor to draw up a trust fund to ensure both Lovejoy’s future and that of likeable restauranteurs the Vincent’s in a new West End premises. Sadly Mrs Chesney passes away before the fund can be finalised and it’s left in the hands of her stern sister Angela (Catherine Lacey) as to whether her dying wishes are carried out.

Ronnie Ronalde with the them from Innocent Sinners 1958 :-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?x-yt-cl=85114404&x-yt-ts=1422579428&v=697ijtKw98w&feature=player_detailpage#t=5