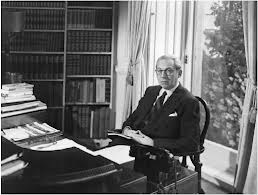

Alexander Korda was born on September 16, 1893 atTurkeve on the Great Hungarian Plain. He was the oldest of three sons. As a young boy, his sight was damaged by the improper treatment of an eye condition. Throughout his life he always wore thick glasses. Despite this detriment, he was a voracious reader, and acquired a near-photographic memory. He also mastered about a half-dozen languages, and was known to be a brilliant (some say “hypnotic”) conversationalist.

Age age thirteen his father died and shortly afterwards he went to Budapest. There he became a short story writer for a daily newspaper.

In 1911 he out to start a career in films and spent several months in Paris, doing odd jobs in the Pathé studio — at the time, the most advanced film factory in the world. He returned to Hungary and joined a film company in Budapest.

Though the Hungarian film industry was in its infancy, the country would produce a surprisingly rich heritage of film. Influential filmmakers like Alexander Korda, Michael Curtiz, and George Cukor were Hungarian. The country also boasted the world’s first film journal. And at this period, Korda became one of the most important figures in the formative years of Hungary’s film community.

Korda managed to raise finance and built his own studio in a suburb of Budapest where the Mafilm Studios are today. Though Korda served as director, he also served as executive producer by overseeing all production activity at his impressive company. In 1919, he assisted the sCommunist government (though Korda was not a member of the Communist party) when it made Hungary the first nationalised film industry in the world. When the Communist government fell and was replaced by the right-wing “White Terror” regime, Korda was briefly imprisoned. In November 1919, he left Hungary with his actress wife Maria. He would never again return to his homeland.

He then made his way to Vienna to join the Sascha Film Company. Desperately seeking his independence, he moved to Berlin to form his own company Korda-Film, directing film vehicles for his wife Maria Corda. His films were well-received, and led to an offer from the First National studios in Hollywood for both Kordas to come to America.

In Los Angeles had directed at First National and Fox. The films were received half-heartedly by the public, and Korda was dissatisfied with the results. He asked Fox studios to release him from his contract, in 1930 — thus ending his career as a Hollywood director.

Disillusioned, he returned to Europe, determined not to return to Hollywood, except as his own producer and studio boss. After making several important films in Paris and Germany, he moved to England in 1931. At that time the English film industry was in a depressed state, dominated by American films. Most English production companies made what were called “quota quickies.” These films were often cheaply made movies used solely to fill screens at a time when the British government mandated that British cinems must show a certain percentage of British-made films.

Korda felt that the only way to bring the English film industry to prominence would be by concentrating on quality films. Alexander Korda organised London Film Productions, and risked everything on a deceptively-lavish movie The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933) starring Charles Laughton and Elsa Lanchester. The film became a worldwide blockbuster.

Following the success of this film, Korda was hailed as the saviour of the British film industry. On the strength of this film, he was also able to land an American distribution deal with United Artists.

Korda constructed the stately Denham Film Studios on a 165-acre estate outside London. He also established his own stable of contract actors – and very impressive they were – including Leslie Howard, Merle Oberon (who became the second Mrs. Korda in 1939), Wendy Barrie, Robert Donat, Maurice Evans, and Vivien Leigh.

Some of his more ambitious films included Rembrandt (1936), which he also directed; Things to Come (1936) a $1.5 million adaptation of the H. G. Welles book; and The Thief of Bagdad (1940).

While Britain was war-torn in the early 1940s, Korda took up an extended residence in the United States.

In March 1943, Korda entered into a merger between his independent company London Film Productions and MGM-British. Korda would become the new executive producer of the English division of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.He returned to England. However, his dissatisfaction with the deal brought about his resignation in 1946.

Korda then with his London Films, bought a controlling interest in British Lion Films which was involved in such productions as The Third Man (1949).

In 1948 he received an advance payment of £375,000, the largest single payment received by a British film company, for three movies, An Ideal Husband (1947), Anna Karenina (1948) and Mine Own Executioner (1948). He released three other films, Bonnie Prince Charlie (1948), The Winslow Boy (1948) and The Fallen Idol (1948). Some of these films did well but others were expensive failures, and Korda was badly hurt by the trade war between the British and American film industries in the late 1940s. In 1948 Korda signed a co-production deal with David O. Selznick.

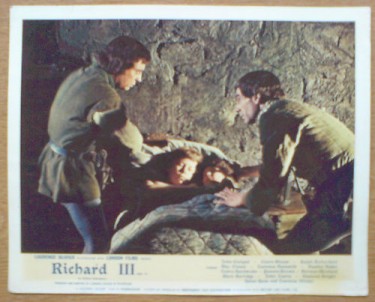

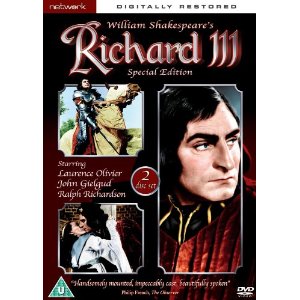

Korda did recover in part due to a ₤3 million loan British Lion received from the National Film Finance Corporation. In 1954 he received ₤5 million from the City Investing Corporation of New York, enabling him to keep producing movies until his death. The last film with Korda’s involvement was Laurence Olivier’s adaptation of Richard III (1955).

A draft screenplay of what became The Red Shoes was written by Emeric Pressburger in the 1930s for Korda and intended as a vehicle for his future wife Merle Oberon. The screenplay was bought by Michael Powell and Pressburger who made it for J. Arthur Rank. During the 1950s, Korda reportedly expressed interest in producing a James Bond film based upon Ian Fleming’s novel Live and Let Die but no agreement was ever reached.

He died at the age of 62 in London of a heart attack and was cremated. His ashes are at Golders Green Crematorium in London.

There are not many so called ‘giants’ in any industry but that work could sum up Aleaxander Korda – The Man who built Denham Film Studios and very nearly pulled it off and put British film studios on a par with Hollywood.

Sadly Denham with its sheer size was forced to close in 1952 and now it is not easy to know where it was. I am pleased to say that I know where it is !!! – and as a film lover it is a place that is very special to me. I do drive past and look when I am down that way.