Walt Disney had huge faith in Perce Pearce both in his film making skills and his ability to get things done. He entrusted Perce to come to England and supervise his first all live action films at Denham Film Studios – Treasure Island and The Story of Robin Hood being the vital and first ones.

Perce Pearce’s career at this point took a major turn: he began working in live action, serving as Walt’s associate producer on Song of the South and So Dear to My Heart before moving to England to shepherd Disney’s first entirely live-action features (Treasure Island, The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men, The Sword and the Rose, Rob Roy the Highland Rogue) onto the screen. In other words, Walt repeatedly chose Pearce to act as his surrogate.

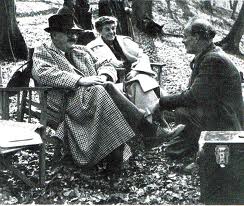

Above: Walt Disney with his family on the set of Treasure Island during their visit here in 1949. Bobby Driscoll one of the stars of the film with them too. This shot is actually on one of the sets at Denham Film Studios.

There may have been a bit of typecasting when Walt sent Pearce to England—he was the son of English immigrants—but what was undoubtedly more important was Pearce’s adaptability, and his willingness to respond to the demands Walt made on him. Throughout the 1940s and ’50s, people who had joined the Disney staff to work on animated cartoons followed similar paths, moving into live action or, later, into television or designing attractions for Disneyland. Ben Sharpsteen was an animator, then a director of short cartoons and feature sequences, and ultimately the “supervising director”—that is, Walt’s man on the ground—of Fantasia, Dumbo, and other features. But then, as Walt’s interest turned toward the True-Life Adventures and the People and Places series, he took Sharpsteen away from animation and put him in charge of those live-action films. Likewise, the director James Algar moved from animation into directing the True-Lifes.

From all appearances, Perce Pearce adapted well to his life in England—in stories about him that I turned up during work on The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, he sounds like a true English eccentric. There’s no telling if such stress contributed to Pearce’s early death in 1956, but it couldn’t have helped.

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: filmsofthefifties.com/perce-pearce-walt-disneys-trusted-producer/ […]